Researchers Examining How Dogs Got To Americas

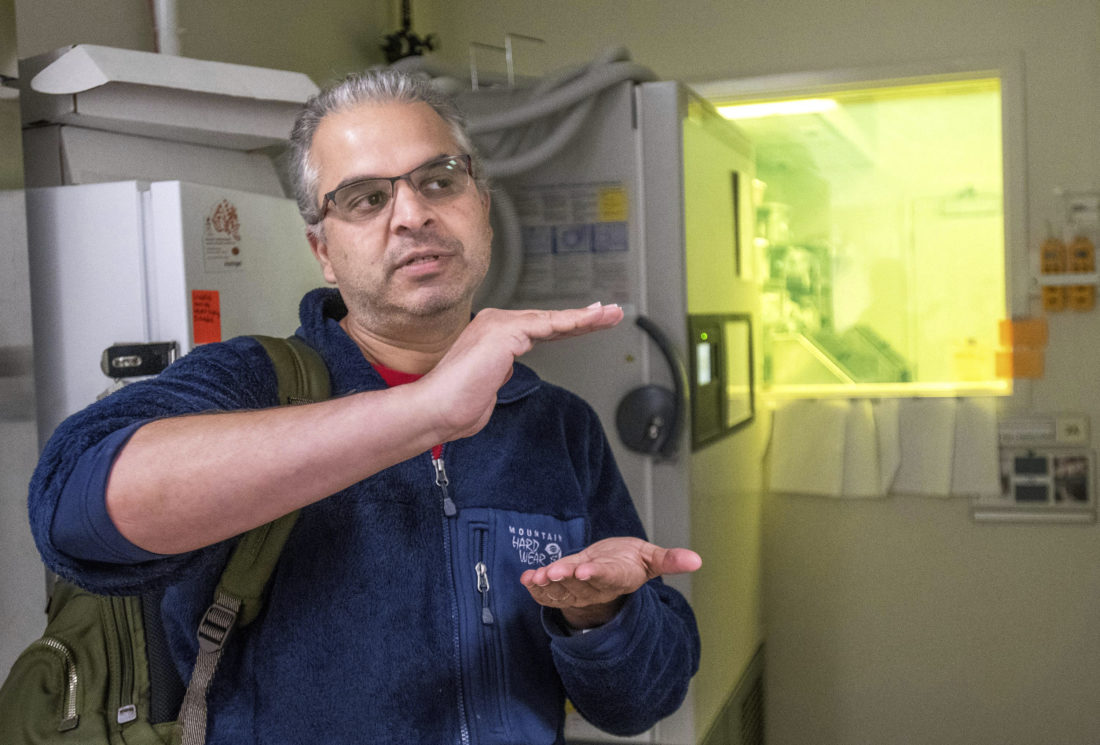

Ripan Malhi, a professor in anthropology, talks about his research outside the clean room where he collected canine DNA in the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology on the University of Illinois campus in Urbana, Ill. Malhi says that the genetic code evidence they have gathered tells us not only about dogs, but potentially about humans who crossed a land bridge that once existed between Siberia and Alaska. Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette via AP

URBANA, Ill. (AP) — Your poodle may have a French pedigree, but Siberia played a major role in introducing dogs to the Americas.

That’s part of the research conducted at the University of Illinois and the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, based on dog remains, including two dogs buried back to back in an Illinois site just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

That loving, ceremonial burial and about 50 fossilized dogs help tell the story, The News-Gazette reports .

That genetic code tells us not only about dogs, but potentially about humans who crossed a land bridge that once existed between Siberia and Alaska, said Ripan Malhi, a professor in anthropology and at the School of Integrative Biology.

The Illinois State Archaeological Survey had found several sites with dogs in them.

Not wanting to destroy valuable scientific and cultural relics, Malhi’s team took samples from domesticated dogs that could be close to 10,000 years old, probably the oldest in America.

“The amount removed is about the size of a (dental) cavity,” he said.

Malhi worked closely with Kelsey Witt Dillon, who led the mitochondrial DNA genome work, following the dogs’ maternal line, as a graduate student here. (She’s now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California-Merced.)

In a clean room — not a trace of contaminants — the researchers extracted the DNA. It was then sequenced in another lab to create a “genomic library.”

“The DNA will give us millions of DNA bits,” Malhi said, some of them contaminated long ago by microbes or even human interference.

These first dogs in the Americas arrived from Siberia, Malhi said, and largely disappeared after European contact, an extreme version of the population decline with Native Americans after contact.

During the Ice Age (lasting until about 14,500 years ago), sea levels were lower and the region between western Siberia and eastern Alaska was all land, rather than the Bering Strait we know today. The region is known as “Beringia,” and people (and dogs) were able to cross the land bridge because of this lower sea level, Witt Dillon added.

Scientists debate how exactly native dogs generally fell out of the gene pool: Our ancestors may have killed them to prevent inter-breeding with the dogs they’d already bred to hunt and herd, or they could have been eaten in times of famine.

Disease is the cause that comes up most often, since the same happened to Native Americans.

In the journal “Science,” the researchers argued the first dogs in the Americas were not domesticated North American wolves.

Most likely, they wrote, the dogs followed companion humans over a land bridge that once connected North Asia through Siberia into the Americas.

At an archaeological site near Cahokia called Janey B. Goode, other researchers found dogs with marks on their shoulders.

Malhi said the marks could mean that the dogs were not just our best friends but our co-workers, helping to pull carts of supplies or so other sort of work similar to their continued use with sleds in the Northwest.

Malhi’s specialty is tracing genetic history, so his articles have titles like “Distribution of Y chromosomes among native North Americans: a study of Athapaskan population history.”

He has worked closely with First Nations peoples in British Columbia and Alaska, including studying an invaluable food resource, the salmon.

Nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA tell stories in different ways.

Nuclear DNA “is the type of DNA most people probably think of — your 23 pairs of chromosomes are all nuclear DNA, and you inherit one half of them from your mother and one half of them from your father,” Witt Dillon explained.

“Your mitochondrial DNA is inherited from your mother,” she said, “and is found in many more copies per cell than your nuclear DNA, so it’s easier to find in ancient DNA samples, which are usually degraded and fragmented.”

There are questions of when and where dogs were domesticated.

“Dogs were likely domesticated between 15,000 and 21,000 years ago, somewhere in Europe or Asia,” Witt Dillon said. “Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Central Asia have all been suggested as places where dogs originated, but we don’t have a clear answer yet.”

Possibly dogs arose in several “birth” places.

By the way, that poop that ends every dog walk? A pain to you, but of great value to science as fossilized coprolites.

UI graduate anthropology student Karthik Yarlagadda is looking at the microbiomes in the coprolites, working with Malhi.

In modern studies, he knows, tested samples contain a large number of microbes that reflect a number of factors, including the host’s genetics, diet and environment.

“Because the coprolites represent an ancient fecal sample, they likely still contain some amount of the residual DNA from the microbes that lived in the dogs at that time. This is particularly interesting because ancient microbiomes give us additional insight into an individual’s life history,” Yarlagadda said.