Civil War Veteran Endures Twist Of Fate

- Portland Town Museum curator Rob Pawlak is shown at the museum building. File photo

- A knife used by Charles Pecor, a Civil War Veteran in the New York 112 Volunteer Infantry Regiment, is on display as well as a spoon, and a bible he had in his possession at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. P-J Photo by Michael Zabrodsky

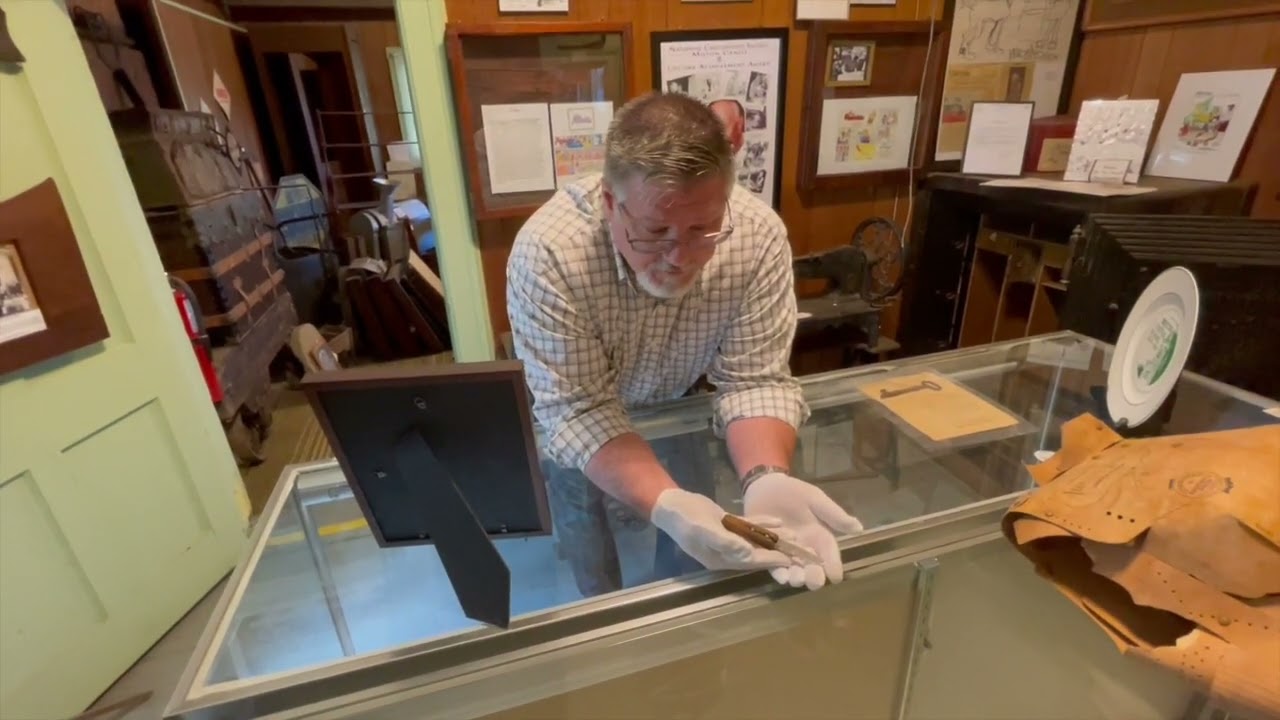

- Rob Pawlak, town of Portland Museum curator, holds a knife used by Charles Pecor, a Civil War Veteran in the New York 112 Volunteer Infantry Regiment. P-J Photo by Michael Zabrodsky

Portland Town Museum curator Rob Pawlak is shown at the museum building. File photo

PORTLAND — How does history become more interesting?

Give it a dose of irony.

That is what happened in the case of town of Portland native Charles Pecor.

According to Robert Pawlak, town of Portland Museum curator, Pecor was a Civil War Veteran in the New York 112 Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was captured by the Confederate Army during the Battle of Cold Harbor, from May 31 to June 12 1864, in Hanover County, Va. Receiving a letter from the regimental adjutant attesting to his death, his parents began burial plans.

But he wasn’t dead, just not heard from.

A knife used by Charles Pecor, a Civil War Veteran in the New York 112 Volunteer Infantry Regiment, is on display as well as a spoon, and a bible he had in his possession at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. P-J Photo by Michael Zabrodsky

Pawlak said Pecor was taken to Libby Prison in Richmond, Va., and then transferred to Andersonville Prison in Georgia where Pecor spent 9.5 months. At Andersonville, Pecor had in his possession a knife, spoon, and bible which are on display at the museum.

Dictionary.com states that irony is a state of affairs or an event that seems deliberately contrary to what one expects and is often amusing as a result.

When his parents found out he was alive, they made plans to get him back from the Confederacy. Pawlak said the Confederacy was not repatriating prisoners because the Union Army would repatriate slaves that had been freed by the union.

The family, Pawlak noted, thought Pecor was aboard the steamboat Sultana riding up the Mississpippi River.

Then tragedy struck the steamer.

Rob Pawlak, town of Portland Museum curator, holds a knife used by Charles Pecor, a Civil War Veteran in the New York 112 Volunteer Infantry Regiment. P-J Photo by Michael Zabrodsky

Battlefields.org, revealed that “On April 23, 1865, the vessel docked in Vicksburg, Miss. to address issues with the boiler during a routine journey from New Orleans. While in port, it was contracted by the U.S. Government to carry former Union prisoners of war from Confederate prisons, such as Andersonville in Georgia back into Northern territory. In order to fulfill the lucrative contract, J. Cass Mason, the Sultana’s captain, opted to patch the leaky boiler rather than complete more extensive and time-consuming repairs. Fearing that his colleagues were taking bribes to transport prisoners on other boats, Union Army Capt. George Williams, who oversaw the operation, hastily ordered that all former prisoners at the parole camp and hospital at Vicksburg be transported on the Sultana. Although it was designed to only hold 376 people, more than 2,000 Union troops were crowded onto the steamboat — more than five times its legal carrying capacity. Despite concerns of overloading from several officers, Williams refused to divide the men, insisting that they travel on one vessel.

“The Sultana steamed north up the Mississippi, but the severe overcrowding and faster river current caused by the spring thaw put increased pressure on its newly patched boilers. Shortly after leaving Memphis, Tennessee on April 27th, the overstrained boilers exploded, blowing apart the center of the boat and starting an uncontrollable fire. Many of those who were not killed immediately perished as they tried to swim to shore. Of the initial survivors, 200 later died from burns sustained during the incident. Researchers indicate that 1,195 of the 2,200 passengers and crew died, making the Sultana incident the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. history.”

Again, Pecor’s parents thought he died aboard the steamboat Sultana during the explosion.

On the contrary.

“Charles is not dead,” Pawlak said. “He was down in Florida and took a train on up and arrived in the hills above Brocton at about 2:30 in the morning. And then he walked down to the family farm arriving between 4:30 and 5:30 in the morning and decided against waking everybody up and crawled into the family barn and slept on a funny looking box next to a funny looking stone.”

Pawlak added the family found him the next morning sleeping on his casket next to his tombstone. “They were going to be burying him later that day and kind of surprised to find their son, there alive.”

According to ancestry.com, Pecor was born Jan. 20, 1843 and died on April 13, 1909 in Portland.